Editor’s Note: This is the second article of a three-part series about the challenges facing the Colombian Economy, authored by Michael Puscar. You can read the first article here. Puscar is a lifelong entrepreneur and the founder of GITP Ventures, an early stage investment group based in Medellin, Colombia.

Rebooting the Colombian Economy

In last week’s article, we established the vulnerabilities of the Colombian economic engine, an export-driven economy that is heavily dependent upon commodity prices.

All commodity-based, export economies are vulnerable to rapid changes in commodity prices, but with 50% of the country’s exports in the volatile energy sector (petroleum and coal), Colombia’s vulnerabilities are particularly profound. Worldwide production of both oil and coal has steadily risen, while consumption has fallen as economies have slowed, resulting in a steep drop in prices.

The drop in prices has consequently caused investment in the Colombian energy sector by companies to grind to a halt, dampening foreign investment and thereby putting downward pressure on the Colombian peso. With falling tax revenues, the Colombian government raised the country’s national IVA (value-added tax), a short-sighted action that even further discourages foreign investment and will put even more pressure on the peso.

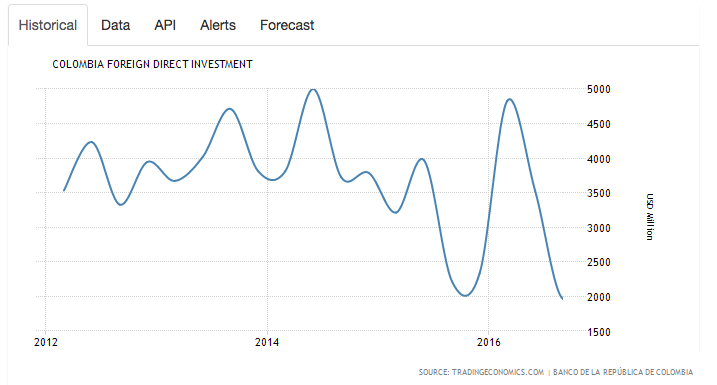

As the following chart shows, FDI (foreign direct investment) in Colombia dropped by 16% year over year and is poised to drop even further.

When energy prices were high, Colombia’s cities boomed. More public projects were funded, unemployment dropped, and tax revenue was plentiful. However the effects of that boom were disproportionately enjoyed by Colombia’s wealthy class and cities.

This wealth and income disparity has caused a mass migration from rural areas to urban areas, creating new problems for the country. According to the World Economic Forum, with data provided by the United Nations, Colombia’s second largest city of Medellín is now the third most densely populated city in the world, with an average of 19,700 people per square km. Only Dhaka in Bangladesh and Mumbai in India ranked higher.

Colombia’s cities were and are woefully unprepared for this migration, in particular the country’s education system, leaving students with inadequate schooling at a time when it is needed most. Both Bogotá and Medellín, Colombia’s two largest cities, have also been plagued in recent years with traffic issues and pollution.

This migration could not have come at a worse time, as the key to the country’s economic recovery likely will rely upon rural and agricultural projects.

For Colombia’s poor, the barriers to escape poverty must seem insurmountable. In a healthy economy, domestic consumption and small business ventures can provide an escape valve for the lower class. However sky high lending rates, well above 20% annually, and a regressive tax system that unfairly punishes low income citizens makes that escape nearly impossible.

According to a study by Colombian news magazine La Semana, 77% of Colombia’s land is owned by 13% of its population, and 3.6% of that 13% own 30% of the land. Without property, obtaining loans and liquidity to start new businesses is not possible. With the lower class, and rural areas in particular, unable to meaningfully participate in the economy, the country is left to rely on a small subset of the population to power the recovery.

And the tax revenue from energy prices that powered Colombia’s economic recovery increasingly appears to be a distant memory, squeezed between increased petroleum and coal production in the United States and a worldwide boom in clean energy technologies.

The situation, while dire, represents a great opportunity. Despite the issues, Colombia is a country with an abundance of natural resources, varied climates for raising livestock and agriculture, a young population and is located in a geographically desirable location.

The country’s economy needs a reboot, and a change in direction could not only lift the country out of its slow-motion economic crisis but also position it as a leader in the new economy.

Next week, in the third article in this three-part series, Puscar will discuss solutions to the forthcoming slow motion Colombian economic crisis.